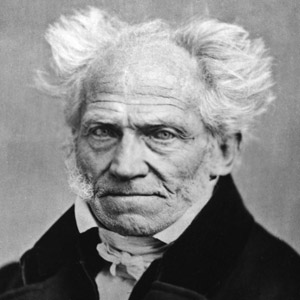

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) was a German philosopher who was born in the city of Danzig. He is best known for his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation, which he expanded in 1844. He was often referred to as “the philosopher of pessimism,” although the focus of his work was on finding a way to find to overcome the fundamentally painful human condition. Schopenhauer was among the first thinkers in Western philosophy to share and affirm significant tenets of Eastern philosophy, having initially arrived at similar conclusions as the result of his own philosophical work. His writing on aesthetics, morality, and psychology have influenced thinkers and artists throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Quotes by Arthur Schopenhauer…

Nothing can trouble him more, nothing can move him, for he has cut all the thousand cords of will which hold us bound to the world… as desire, fear, envy, anger, drag us here and there in constant pain. He now looks back smiling and at rest on the delusions of the world, which once were able to move and agonize his spirit also.

Nothing will protect us from external compulsion as much as the control of ourselves, and, as Seneca says, to submit yourself to reason is the way to make everything else submit to you.

The man who comes into the world with the notion that he is really going to instruct it in matters of the highest importance, may thank his stars if he escapes with a whole skin.

Take the case of a large number of people who have gathered together for the purpose of carrying out some practical project. If there are two rascals among them, they will recognize each other quickly, as if each wore a similar badge, and they will at once conspire for some selfishness or treachery… It is really curious to see how two such men, especially if they are morally and intellectually inferior, will recognize each other at first sight, with what zeal they will try to become friends, how affably and cheerfully they will rush to greet each other.

We often try to banish the gloom and despondency of the present by speculating upon our chances of success in the future; a process which leads us to invent a great many unreal hopes. Every one of them contains the seed of illusion, and disappointment is inevitable when our hopes are shattered.

I have said that people are rendered sociable by their inability to endure solitude, that is to say, their own society. They become sick of themselves. Their mind is wanting in flexibility; it has no movement of its own, so they try to give it some — by drink, for instance… They are always looking for some form of excitement, of the strongest kind they can bear — the excitement of being with people of like nature with themselves; and if they fail in this, their mind sinks by its own weight, and they fall into grievous lethargy.

Whether we are in a pleasant or a painful state depends, finally, upon the kind of matter that pervades and engrosses our consciousness.

Suppose that, with the exception of some sore or painful spot, we are physically in a sound and healthy condition. The pain of this one spot will completely absorb our attention, causing us to lose the sense of general well-being, and destroying our comfort in life. In the same way, when all our affairs but one turn out as we wish, the single instance in which our aims are frustrated is a constant trouble to us, even though it is something quite trivial.

A man is best off if he is thrown upon his own resources, and can be all in all to himself, and Cicero goes so far as to say that a man who is in this condition cannot fail to be very happy.

With a large number of people, it is quite evident that their power of sight wholly predominates over their power of thought; they seem to be conscious of their existence only when they are making a noise.